Running Python

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I run Python programs?

Objectives

Be able to start and quit Python

Use Python interactively through the Read-Eval-Print-Loop (REPL)

Python is a programming language, a collection of syntax rules, keywords that can be used to specify operations to be executed by a computer. But how to go from these instructions to actual operations carried out by a computer? This translation and execution is the job of the Python runtime, a piece of software that, given some instructions in Python, translates them into machine code and runs them. The Python runtime is, most of the time, called Python, confusign the software that interprets the language with the language itself. This language shortcut is harmless most of the time, but it’s good to know that this it is a shortcut.

Starting Python

You can start Python (understand the Python runtime) through the command line or through an application called

Anaconda Navigator. Anaconda Navigator is included as part of the Anaconda Python distribution.

macOS - Command Line

To start Python you will need to access the command line through the Terminal. There are two ways to open Terminal on Mac.

- In your Applications folder, open Utilities and double-click on Terminal

- Press Command + spacebar to launch Spotlight. Type

Terminaland then double-click the search result or hit Enter

After you have launched Terminal, type the command to start Python

$ python

Windows Users - Command Line

To start Python you will need to access the Anaconda Prompt.

Press Windows Logo Key and search for Anaconda Prompt, click the result or press enter.

After you have launched the Anaconda Prompt, type the command:

$ python

GNU/Linux Users - Command Line

To start Python you will need to access the terminal emulator. You can usually find it under “Accessories”.

After you have launched the terminal emulator, type the command:

$ python

Anaconda Navigator

To start Python from Anaconda Navigator you must first start Anaconda Navigator (click for detailed instructions on macOS, Windows, and Linux). You can search for Anaconda Navigator via Spotlight on macOS (Command + spacebar), the Windows search function (Windows Logo Key) or opening a terminal shell and executing the anaconda-navigator executable from the command line.

After you have launched Anaconda Navigator, click the Launch button

under “CMD.exe prompt”. You may need to scroll down to find it.

Here is a screenshot of an Anaconda Navigator page similar to the one that should open on either macOS or Windows.

First steps with Python

To start off with, you can think of Python as a fancy calculator. You issue commands, hit ENTER, and the result appears on the line below.

Give some of the examples below a try. Type the lines preceded by

>>> or ... and hit ENTER between each one.

Try to guess what these little snippets of Python do, but don’t try to understand the details of them yet - it will be clear to you by the end of this course.

>>> 1 + 6

7

>>> a = 2

>>> b = 3

>>> a + b

5

>>> print("Just printing this on the screen")

Just printing this on the screen

>>> word = "Hello"

>>> len(word)

4

>>> for word in ["Leeds", "Munich", "Marseille"]:

... print("City name has", len(word), "letters in it.")

...

...

City name has 5 letters in it.

City name has 6 letters in it.

City name has 9 letters in it.

>>> for word in ["London", 3, "Marseille"]:

... print("City name has", len(word), "letters in it.")

...

City name has 6 letters in it.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module>

TypeError: object of type 'int' has no len()

Quitting

You can quit Python by typing

>>> quit()

then ENTER.

The REPL

Running Python interactively from the command line, one command after the other, is commonly referred to as using the Read-Eval-Print-Loop (REPL, pronounced “repel”). Indeed, when doing so, Python reads the command, evaluates it, prints the result and loops (goes back to waiting for the next command).

The REPL allows for very quick feedback while drafting a Python program or exploring data. It makes it very easy to test a few lines of code and build programs iteratively.

Key Points

Python is just another program on your computer.

Python can be used interactively through a Read-Eval-Print-Loop.

Using Python interactively is great to manipulate data and exploratory work.

Variables and Types

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I store data in programs?

What kinds of data do programs store?

How can I convert one type to another?

Objectives

Write programs that assign scalar values to variables and perform calculations with those values.

Correctly trace value changes in programs that use scalar assignment.

Explain key differences between integers and floating point numbers.

Explain key differences between numbers and character strings.

Use built-in functions to convert between integers, floating point numbers, and strings.

Use variables to store values.

- Variables are names for values.

- In Python the

=symbol assigns the value on the right to the name on the left. - The variable is created when a value is assigned to it.

-

Here, Python assigns an age to a variable

ageand a name in quotes to a variablefirst_name.age = 42 first_name = 'Ahmed' - Variable names

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

_(typically used to separate words in long variable names) - cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive (age, Age and AGE are three different variables)

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

- Variable names that start with underscores like

__alistairs_real_agehave a special meaning so we won’t do that until we understand the convention.

Use print to display values.

- Python has a built-in function called

printthat prints things as text. - Call the function (i.e., tell Python to run it) by using its name.

- Provide values to the function (i.e., the things to print) in parentheses.

- To add a string to the printout, wrap the string in single or double quotes.

- The values passed to the function are called arguments

print(first_name, 'is', age, 'years old')

Ahmed is 42 years old

printautomatically puts a single space between items to separate them.- And wraps around to a new line at the end.

Variables must be created before they are used.

- If a variable doesn’t exist yet, or if the name has been mis-spelled, Python reports an error. (Unlike some languages, which “guess” a default value.)

print(last_name)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-c1fbb4e96102> in <module>()

----> 1 print(last_name)

NameError: name 'last_name' is not defined

- The last line of an error message is usually the most informative.

- We will look at error messages in detail later.

Variables can be used in calculations.

- We can use variables in calculations just as if they were values.

- Remember, we assigned the value

42toagea few lines ago.

- Remember, we assigned the value

age = age + 3

print('Age in three years:', age)

Age in three years: 45

Use an index to get a single character from a string.

- The characters (individual letters, numbers, and so on) in a string are

ordered. For example, the string

'AB'is not the same as'BA'. Because of this ordering, we can treat the string as a list of characters. - Each position in the string (first, second, etc.) is given a number. This number is called an index or sometimes a subscript.

- Indices are numbered from 0.

- Use the position’s index in square brackets to get the character at that position.

atom_name = 'helium'

print(atom_name[0])

h

Use a slice to get a substring.

- A part of a string is called a substring. A substring can be as short as a single character.

- An item in a list is called an element. Whenever we treat a string as if it were a list, the string’s elements are its individual characters.

- A slice is a part of a string (or, more generally, any list-like thing).

- We take a slice by using

[start:stop], wherestartis replaced with the index of the first element we want andstopis replaced with the index of the element just after the last element we want. - Mathematically, you might say that a slice selects

[start:stop). - The difference between

stopandstartis the slice’s length. - Taking a slice does not change the contents of the original string. Instead, the slice is a copy of part of the original string.

atom_name = 'sodium'

print(atom_name[0:3])

sod

Use the built-in function len to find the length of a string.

print(len('helium'))

6

- Nested functions are evaluated from the inside out, like in mathematics.

Python is case-sensitive.

- Python thinks that upper- and lower-case letters are different,

so

Nameandnameare different variables. - There are conventions for using upper-case letters at the start of variable names so we will use lower-case letters for now.

Use meaningful variable names.

- Python doesn’t care what you call variables as long as they obey the rules (alphanumeric characters and the underscore).

flabadab = 42

ewr_422_yY = 'Ahmed'

print(ewr_422_yY, 'is', flabadab, 'years old')

- Use meaningful variable names to help other people understand what the program does.

- The most important “other person” is your future self.

Swapping Values

Fill the table showing the values of the variables in this program after each statement is executed.

# Command # Value of x # Value of y # Value of swap # x = 1.0 # # # # y = 3.0 # # # # swap = x # # # # x = y # # # # y = swap # # # #Solution

# Command # Value of x # Value of y # Value of swap # x = 1.0 # 1.0 # not defined # not defined # y = 3.0 # 1.0 # 3.0 # not defined # swap = x # 1.0 # 3.0 # 1.0 # x = y # 3.0 # 3.0 # 1.0 # y = swap # 3.0 # 1.0 # 1.0 #These three lines exchange the values in

xandyusing theswapvariable for temporary storage. This is a fairly common programming idiom.

Slicing practice

What does the following program print?

atom_name = 'carbon' print('atom_name[1:3] is:', atom_name[1:3])Solution

atom_name[1:3] is: ar

Slicing concepts

- What does

thing[low:high]do?- What does

thing[low:](without a value after the colon) do?- What does

thing[:high](without a value before the colon) do?- What does

thing[:](just a colon) do?- What does

thing[number:some-negative-number]do?- What happens when you choose a

highvalue which is out of range? (i.e., tryatom_name[0:15])Solutions

thing[low:high]returns a slice fromlowto the value beforehighthing[low:]returns a slice fromlowall the way to the end ofthingthing[:high]returns a slice from the beginning ofthingto the value beforehighthing[:]returns all ofthingthing[number:some-negative-number]returns a slice fromnumbertosome-negative-numbervalues from the end ofthing- If a part of the slice is out of range, the operation does not fail.

atom_name[0:15]gives the same result asatom_name[0:].

Every value has a type.

- Every value in a program has a specific type.

- Integer (

int): represents positive or negative whole numbers like 3 or -512. - Floating point number (

float): represents real numbers like 3.14159 or -2.5. - Character string (usually called “string”,

str): text.- Written in either single quotes or double quotes (as long as they match).

- The quote marks aren’t printed when the string is displayed.

Use the built-in function type to find the type of a value.

- Use the built-in function

typeto find out what type a value has. - Works on variables as well.

- But remember: the value has the type — the variable is just a label.

print(type(52))

<class 'int'>

fitness = 'average'

print(type(fitness))

<class 'str'>

Types control what operations (or methods) can be performed on a given value.

- A value’s type determines what the program can do to it.

print(5 - 3)

2

print('hello' - 'h')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-67f5626a1e07> in <module>()

----> 1 print('hello' - 'h')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

You can use the “+” and “*” operators on strings.

- “Adding” character strings concatenates them.

full_name = 'Ahmed' + ' ' + 'Walsh'

print(full_name)

Ahmed Walsh

- Multiplying a character string by an integer N creates a new string that consists of that character string repeated N times.

- Since multiplication is repeated addition.

separator = '=' * 10

print(separator)

==========

Strings have a length (but numbers don’t).

- The built-in function

lencounts the number of characters in a string.

print(len(full_name))

11

- But numbers don’t have a length (not even zero).

print(len(52))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-f769e8e8097d> in <module>()

----> 1 print(len(52))

TypeError: object of type 'int' has no len()

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

- Cannot add numbers and strings.

print(1 + '2')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-4-fe4f54a023c6> in <module>()

----> 1 print(1 + '2')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

- Not allowed because it’s ambiguous: should

1 + '2'be3or'12'? - Some types can be converted to other types by using the type name as a function.

print(1 + int('2'))

print(str(1) + '2')

3

12

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

- Integers and floating-point numbers can be mixed in arithmetic.

- Python 3 automatically converts integers to floats as needed.

print('half is', 1 / 2.0)

print('three squared is', 3.0 ** 2)

half is 0.5

three squared is 9.0

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

- If we make one cell in a spreadsheet depend on another, and update the latter, the former updates automatically.

- This does not happen in programming languages.

first = 1

second = 5 * first

first = 2

print('first is', first, 'and second is', second)

first is 2 and second is 5

- The computer reads the value of

firstwhen doing the multiplication, creates a new value, and assigns it tosecond. - After that,

seconddoes not remember where it came from.

Automatic Type Conversion

What type of value is 3.25 + 4?

Solution

It is a float: integers are automatically converted to floats as necessary.

result = 3.25 + 4 print(result, 'is', type(result))7.25 is <class 'float'>

Choose a Type

What type of value (integer, floating point number, or character string) would you use to represent each of the following? Try to come up with more than one good answer for each problem. For example, in # 1, when would counting days with a floating point variable make more sense than using an integer?

- Number of days since the start of the year.

- Time elapsed from the start of the year until now in days.

- Serial number of a piece of lab equipment.

- A lab specimen’s age

- Current population of a city.

- Average population of a city over time.

Solution

The answers to the questions are:

- Integer, since the number of days would lie between 1 and 365.

- Floating point, since fractional days are required

- Character string if serial number contains letters and numbers, otherwise integer if the serial number consists only of numerals

- This will vary! How do you define a specimen’s age? whole days since collection (integer)? date and time (string)?

- Choose floating point to represent population as large aggregates (eg millions), or integer to represent population in units of individuals.

- Floating point number, since an average is likely to have a fractional part.

Division Types

In Python 3, the

//operator performs integer (whole-number) floor division, the/operator performs floating-point division, and the%(or modulo) operator calculates and returns the remainder from integer division:print('5 // 3:', 5 // 3) print('5 / 3:', 5 / 3) print('5 % 3:', 5 % 3)5 // 3: 1 5 / 3: 1.6666666666666667 5 % 3: 2If

num_subjectsis the number of subjects taking part in a study, andnum_per_surveyis the number that can take part in a single survey, write an expression that calculates the number of surveys needed to reach everyone once.Solution

We want the minimum number of surveys that reaches everyone once, which is the rounded up value of

num_subjects/ num_per_survey. This is equivalent to performing a floor division with//and adding 1. Before the division we need to subtract 1 from the number of subjects to deal with the case wherenum_subjectsis evenly divisible bynum_per_survey.num_subjects = 600 num_per_survey = 42 num_surveys = (num_subjects - 1) // num_per_survey + 1 print(num_subjects, 'subjects,', num_per_survey, 'per survey:', num_surveys)600 subjects, 42 per survey: 15

Use variables to store values.

- Variables are names for values.

- In Python the

=symbol assigns the value on the right to the name on the left. - The variable is created when a value is assigned to it.

-

Here, Python assigns an age to a variable

ageand a name in quotes to a variablefirst_name.age = 42 first_name = 'Ahmed' - Variable names

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

_(typically used to separate words in long variable names) - cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive (age, Age and AGE are three different variables)

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

- Variable names that start with underscores like

__alistairs_real_agehave a special meaning so we won’t do that until we understand the convention.

Use print to display values.

- Python has a built-in function called

printthat prints things as text. - Call the function (i.e., tell Python to run it) by using its name.

- Provide values to the function (i.e., the things to print) in parentheses.

- To add a string to the printout, wrap the string in single or double quotes.

- The values passed to the function are called arguments

print(first_name, 'is', age, 'years old')

Ahmed is 42 years old

printautomatically puts a single space between items to separate them.- And wraps around to a new line at the end.

Variables must be created before they are used.

- If a variable doesn’t exist yet, or if the name has been mis-spelled, Python reports an error. (Unlike some languages, which “guess” a default value.)

print(last_name)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-c1fbb4e96102> in <module>()

----> 1 print(last_name)

NameError: name 'last_name' is not defined

- The last line of an error message is usually the most informative.

- We will look at error messages in detail later.

Variables can be used in calculations.

- We can use variables in calculations just as if they were values.

- Remember, we assigned the value

42toagea few lines ago.

- Remember, we assigned the value

age = age + 3

print('Age in three years:', age)

Age in three years: 45

Use an index to get a single character from a string.

- The characters (individual letters, numbers, and so on) in a string are

ordered. For example, the string

'AB'is not the same as'BA'. Because of this ordering, we can treat the string as a list of characters. - Each position in the string (first, second, etc.) is given a number. This number is called an index or sometimes a subscript.

- Indices are numbered from 0.

- Use the position’s index in square brackets to get the character at that position.

atom_name = 'helium'

print(atom_name[0])

h

Use a slice to get a substring.

- A part of a string is called a substring. A substring can be as short as a single character.

- An item in a list is called an element. Whenever we treat a string as if it were a list, the string’s elements are its individual characters.

- A slice is a part of a string (or, more generally, any list-like thing).

- We take a slice by using

[start:stop], wherestartis replaced with the index of the first element we want andstopis replaced with the index of the element just after the last element we want. - Mathematically, you might say that a slice selects

[start:stop). - The difference between

stopandstartis the slice’s length. - Taking a slice does not change the contents of the original string. Instead, the slice is a copy of part of the original string.

atom_name = 'sodium'

print(atom_name[0:3])

sod

Use the built-in function len to find the length of a string.

print(len('helium'))

6

- Nested functions are evaluated from the inside out, like in mathematics.

Python is case-sensitive.

- Python thinks that upper- and lower-case letters are different,

so

Nameandnameare different variables. - There are conventions for using upper-case letters at the start of variable names so we will use lower-case letters for now.

Use meaningful variable names.

- Python doesn’t care what you call variables as long as they obey the rules (alphanumeric characters and the underscore).

flabadab = 42

ewr_422_yY = 'Ahmed'

print(ewr_422_yY, 'is', flabadab, 'years old')

- Use meaningful variable names to help other people understand what the program does.

- The most important “other person” is your future self.

Swapping Values

Fill the table showing the values of the variables in this program after each statement is executed.

# Command # Value of x # Value of y # Value of swap # x = 1.0 # # # # y = 3.0 # # # # swap = x # # # # x = y # # # # y = swap # # # #Solution

# Command # Value of x # Value of y # Value of swap # x = 1.0 # 1.0 # not defined # not defined # y = 3.0 # 1.0 # 3.0 # not defined # swap = x # 1.0 # 3.0 # 1.0 # x = y # 3.0 # 3.0 # 1.0 # y = swap # 3.0 # 1.0 # 1.0 #These three lines exchange the values in

xandyusing theswapvariable for temporary storage. This is a fairly common programming idiom.

Slicing practice

What does the following program print?

atom_name = 'carbon' print('atom_name[1:3] is:', atom_name[1:3])Solution

atom_name[1:3] is: ar

Slicing concepts

- What does

thing[low:high]do?- What does

thing[low:](without a value after the colon) do?- What does

thing[:high](without a value before the colon) do?- What does

thing[:](just a colon) do?- What does

thing[number:some-negative-number]do?- What happens when you choose a

highvalue which is out of range? (i.e., tryatom_name[0:15])Solutions

thing[low:high]returns a slice fromlowto the value beforehighthing[low:]returns a slice fromlowall the way to the end ofthingthing[:high]returns a slice from the beginning ofthingto the value beforehighthing[:]returns all ofthingthing[number:some-negative-number]returns a slice fromnumbertosome-negative-numbervalues from the end ofthing- If a part of the slice is out of range, the operation does not fail.

atom_name[0:15]gives the same result asatom_name[0:].

Key Points

Use variables to store values.

Use

Variables persist between cells.

Variables must be created before they are used.

Variables can be used in calculations.

Use an index to get a single character from a string.

Use a slice to get a substring.

Use the built-in function

lento find the length of a string.Python is case-sensitive.

Use meaningful variable names.

Every value has a type.

Use the built-in function

typeto find the type of a value.Types control what operations can be done on values.

Strings can be added and multiplied.

Strings have a length (but numbers don’t).

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

Writing and running Python from Spyder

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I write Python programs that persist in time?

How can I use a Python development environment like Spyder?

Objectives

Running a python script from the command line

Starting and quitting Spyder

Writing and executing a simple python script from Spyder.

Going back and forth between script and Python REPL.

Python scripts

So far we’ve worked in the REPL and we cannot save our programs.

Instead of the interactive mode, Python can read a file that contains Python instructions. This file is commonly referred to as a Python script.

Python scripts are plain text files (see below for a discussion about plain vs rich text formats). To create a plain text file, you need to use a text editor. Depending on whether you’re using GNU/Linux, MacOS or Windows, you’ll need different software for that. Click on the box below that corresponds to your situation.

Writing text files with nano on macOS or GNU/Linux

nanois a bare-bones text editor that’s available on most GNU/Linux distributions and macOS.nanoruns inside a terminal emulator. To create a new Python file withnano, start a terminal emulator (“Terminal” app on macOS) and type:

nano myfile.py

Useful commands are described at the bottom of the terminal window. The symbol

^means the Control key. So^Xmeans hold the Control key and press the x key.

Writing text files with notepad on Windows

Here’s how to use notepad on windows

Text vs. Whatever

We usually call programs like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer “text editors”, but we need to be a bit more careful when it comes to programming. By default, Microsoft Word uses

.docxfiles to store not only text, but also formatting information about fonts, headings, and so on. This extra information isn’t stored as characters and doesn’t mean anything to tools likehead: they expect input files to contain nothing but the letters, digits, and punctuation on a standard computer keyboard. When editing programs, therefore, you must either use a plain text editor, or be careful to save files as plain text.

Let’s try to write a simple Python script. Open a new plain text file (with the method described above depending on your operating system), name it for instance myfirstscript.py.

Write the following python code and save the file.

print("hello world")

varint = 1

print("Variable 'varint' is a", type(varint))

varstr = "astring"

print("Variable 'varfl' is a", type(varfl))

Now let’s execute this script. In the terminal (macOS/Linux) or the Anaconda prompt (Windows), type

$ python myfirstscript.py

hello world

Variable 'varint' is a <class 'int'>

Variable 'varstr' is a <class 'str'>

Can you guess what happened? Python read the file, executing each line one after the other. This is equivalent to typing the 5 lines in the REPL, except you wrote them once and for all in the file.

Programming in Python in practice

When programming in Python, you will find yourself working inside a

text editor most of the time, building your program. You can also go

back and forth between the text editor and the REPL to try things out

in an interactive way, for instance if you’re unsure about syntax.

When you’re happy with your program, you can run it with the command

python <yourfile>.py.

This means your need three pieces of software running concurrently:

- A text editor.

- The Python REPL.

- A command-prompt or terminal emulator.

You could go a long way with this, but this quickly goes unwieldly, especially as your programms grow. We now learn about Spyder, which is a software that brings everything under one roof

Using Spyder

Spyder is software that provides a convenient environment to develop Python programs.

You can start it from the Anaconda navigator or from the command line by typing spyder.

On the left is a text editor, on the bottom right a Python REPL. The top right corner is dedicated to displaying documentation.

Spyder is an Integrated Development Environment. It combines a text editor and a python REPL. You can also run Python scripts directly from Spyder by clicking on the green arrow in the taskbar.

In addition, Spyder reports syntax errors in real time, reminds you of the parameters for a given function, includes a debugger, allows to send a selection to the REPL for execution… and more. It’s all about developping in Python in an efficient way.

Creating a new file

- Setting the current dir

- Creating new file

Running the script

Using the REPL

From script to REPL

- Running a line or selection

- Cells

A word on IPython

IPython is a Python REPL that builds on top of the default one to provide more functionalities.

Key Points

Python scripts are plain text files.

Spyder is a software that integrates both a text editor and the Python runtime.

Spyder provides convenience features such as autocompletion, documentation lookup and debugging.

Spyder is one of many options.

Built-in Functions and Help

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I use built-in functions?

How can I find out what they do?

What kind of errors can occur in programs?

Objectives

Explain the purpose of functions.

Correctly call built-in Python functions.

Correctly nest calls to built-in functions.

Use help to display documentation for built-in functions.

Correctly describe situations in which SyntaxError and NameError occur.

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

# This sentence isn't executed by Python.

adjustment = 0.5 # Neither is this - anything after '#' is ignored.

A function may take zero or more arguments.

- We have seen some functions already — now let’s take a closer look.

- An argument is a value passed into a function.

lentakes exactly one.int,str, andfloatcreate a new value from an existing one.printtakes zero or more.printwith no arguments prints a blank line.- Must always use parentheses, even if they’re empty, so that Python knows a function is being called.

print('before')

print()

print('after')

before

after

Every function returns something.

- Every function call produces some result.

- If the function doesn’t have a useful result to return,

it usually returns the special value

None.Noneis a Python object that stands in anytime there is no value.

result = print('example')

print('result of print is', result)

example

result of print is None

Commonly-used built-in functions include max, min, and round.

- Use

maxto find the largest value of one or more values. - Use

minto find the smallest. - Both work on character strings as well as numbers.

- “Larger” and “smaller” use (0-9, A-Z, a-z) to compare letters.

print(max(1, 2, 3))

print(min('a', 'A', '0'))

3

0

Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

maxandminmust be given at least one argument.- “Largest of the empty set” is a meaningless question.

- And they must be given things that can meaningfully be compared.

print(max(1, 'a'))

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-52-3f049acf3762> in <module>

----> 1 print(max(1, 'a'))

TypeError: '>' not supported between instances of 'str' and 'int'

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

roundwill round off a floating-point number.- By default, rounds to zero decimal places.

round(3.712)

4

- We can specify the number of decimal places we want.

round(3.712, 1)

3.7

Functions attached to objects are called methods

- Functions take another form that will be common in the pandas episodes.

- Methods have parentheses like functions, but come after the variable.

- Some methods are used for internal Python operations, and are marked with double underlines.

my_string = 'Hello world!' # creation of a string object

print(len(my_string)) # the len function takes a string as an argument and returns the length of the string

print(my_string.swapcase()) # calling the swapcase method on the my_string object

print(my_string.__len__()) # calling the internal __len__ method on the my_string object, used by len(my_string)

12

hELLO WORLD!

12

- You might even see them chained together. They operate left to right.

print(my_string.isupper()) # Not all the letters are uppercase

print(my_string.upper()) # This capitalizes all the letters

print(my_string.upper().isupper()) # Now all the letters are uppercase

False

HELLO WORLD

True

Use the built-in function help to get help for a function.

- Every built-in function has online documentation.

help(round)

Help on built-in function round in module builtins:

round(number, ndigits=None)

Round a number to a given precision in decimal digits.

The return value is an integer if ndigits is omitted or None. Otherwise

the return value has the same type as the number. ndigits may be negative.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

- Won’t even try to run the program if it can’t be parsed.

# Forgot to close the quote marks around the string.

name = 'Feng

File "<ipython-input-56-f42768451d55>", line 2

name = 'Feng

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

# An extra '=' in the assignment.

age = = 52

File "<ipython-input-57-ccc3df3cf902>", line 2

age = = 52

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

- Look more closely at the error message:

print("hello world"

File "<ipython-input-6-d1cc229bf815>", line 1

print ("hello world"

^

SyntaxError: unexpected EOF while parsing

- The message indicates a problem on first line of the input (“line 1”).

- In this case the “ipython-input” section of the file name tells us that we are working with input into IPython, the Python interpreter used by the Jupyter Notebook.

- The

-6-part of the filename indicates that the error occurred in cell 6 of our Notebook. - Next is the problematic line of code,

indicating the problem with a

^pointer.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

age = 53

remaining = 100 - aege # mis-spelled 'age'

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-59-1214fb6c55fc> in <module>

1 age = 53

----> 2 remaining = 100 - aege # mis-spelled 'age'

NameError: name 'aege' is not defined

- Fix syntax errors by reading the source and runtime errors by tracing execution.

Explore the Python docs!

The official Python documentation is arguably the most complete source of information about the language. It is available in different languages and contains a lot of useful resources. The Built-in Functions page contains a catalogue of all of these functions, including the ones that we’ve covered in this lesson. Some of these are more advanced and unnecessary at the moment, but others are very simple and useful.

Key Points

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

A function may take zero or more arguments.

Commonly-used built-in functions include

max,min, andround.Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

Use the built-in function

helpto get help for a function.Every function returns something.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

Fix syntax errors by reading the source code, and runtime errors by tracing the program’s execution.

Libraries

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I use software that other people have written?

How can I find out what that software does?

Objectives

Explain what software libraries are and why programmers create and use them.

Write programs that import and use modules from Python’s standard library.

Find and read documentation for the standard library interactively (in the interpreter) and online.

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

- A library is a collection of files (called modules) that contains

functions for use by other programs.

- May also contain data values (e.g., numerical constants) and other things.

- Library’s contents are supposed to be related, but there’s no way to enforce that.

- The Python standard library is an extensive suite of modules that comes with Python itself.

- Many additional libraries are available from PyPI (the Python Package Index).

- We will see later how to write new libraries.

Libraries and modules

A library is a collection of modules, but the terms are often used interchangeably, especially since many libraries only consist of a single module, so don’t worry if you mix them.

A program must import a library module before using it.

- Use

importto load a library module into a program’s memory. - Then refer to things from the module as

module_name.thing_name.- Python uses

.to mean “part of”.

- Python uses

- Using

math, one of the modules in the standard library:

import math

print('pi is', math.pi)

print('cos(pi) is', math.cos(math.pi))

pi is 3.141592653589793

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Have to refer to each item with the module’s name.

math.cos(pi)won’t work: the reference topidoesn’t somehow “inherit” the function’s reference tomath.

Use help to learn about the contents of a library module.

- Works just like help for a function.

help(math)

Help on module math:

NAME

math

MODULE REFERENCE

http://docs.python.org/3/library/math

The following documentation is automatically generated from the Python

source files. It may be incomplete, incorrect or include features that

are considered implementation detail and may vary between Python

implementations. When in doubt, consult the module reference at the

location listed above.

DESCRIPTION

This module is always available. It provides access to the

mathematical functions defined by the C standard.

FUNCTIONS

acos(x, /)

Return the arc cosine (measured in radians) of x.

⋮ ⋮ ⋮

Import specific items from a library module to shorten programs.

- Use

from ... import ...to load only specific items from a library module. - Then refer to them directly without library name as prefix.

from math import cos, pi

print('cos(pi) is', cos(pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

Create an alias for a library module when importing it to shorten programs.

- Use

import ... as ...to give a library a short alias while importing it. - Then refer to items in the library using that shortened name.

import math as m

print('cos(pi) is', m.cos(m.pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Commonly used for libraries that are frequently used or have long names.

- E.g., the

matplotlibplotting library is often aliased asmpl.

- E.g., the

- But can make programs harder to understand, since readers must learn your program’s aliases.

Locating the Right Module

You want to select a random character from a string:

bases = 'ACTTGCTTGAC'

- Which standard library module could help you?

- Which function would you select from that module? Are there alternatives?

- Try to write a program that uses the function.

Solution

The random module seems like it could help you.

The string has 11 characters, each having a positional index from 0 to 10. You could use either

random.randrangeorrandom.randintfunctions to get a random integer between 0 and 10, and then pick out the character at that position:from random import randrange random_index = randrange(len(bases)) print(bases[random_index])or more compactly:

from random import randrange print(bases[randrange(len(bases))])Perhaps you found the

random.samplefunction? It allows for slightly less typing:from random import sample print(sample(bases, 1)[0])Note that this function returns a list of values. We will learn about lists in episode 11.

There’s also other functions you could use, but with more convoluted code as a result.

When Is Help Available?

When a colleague of yours types

help(math), Python reports an error:NameError: name 'math' is not definedWhat has your colleague forgotten to do?

Solution

Importing the math module (

import math)

Importing With Aliases

- Fill in the blanks so that the program below prints

90.0.- Rewrite the program so that it uses

importwithoutas.- Which form do you find easier to read?

import math as m angle = ____.degrees(____.pi / 2) print(____)Solution

import math as m angle = m.degrees(m.pi / 2) print(angle)can be written as

import math angle = math.degrees(math.pi / 2) print(angle)Since you just wrote the code and are familiar with it, you might actually find the first version easier to read. But when trying to read a huge piece of code written by someone else, or when getting back to your own huge piece of code after several months, non-abbreviated names are often easier, except where there are clear abbreviation conventions.

There Are Many Ways To Import Libraries!

Match the following print statements with the appropriate library calls.

Print commands:

print("sin(pi/2) =", sin(pi/2))print("sin(pi/2) =", m.sin(m.pi/2))print("sin(pi/2) =", math.sin(math.pi/2))Library calls:

from math import sin, piimport mathimport math as mfrom math import *Solution

- Library calls 1 and 4. In order to directly refer to

sinandpiwithout the library name as prefix, you need to use thefrom ... import ...statement. Whereas library call 1 specifically imports the two functionssinandpi, library call 4 imports all functions in themathmodule.- Library call 3. Here

sinandpiare referred to with a shortened library nameminstead ofmath. Library call 3 does exactly that using theimport ... as ...syntax - it creates an alias formathin the form of the shortened namem.- Library call 2. Here

sinandpiare referred to with the regular library namemath, so the regularimport ...call suffices.Note: although library call 4 works, importing all names from a module using a wildcard import is not recommended as it makes it unclear which names from the module are used in the code. In general it is best to make your imports as specific as possible and to only import what your code uses. In library call 1, the

importstatement explicitly tells us that thesinfunction is imported from themathmodule, but library call 4 does not convey this information.

Importing Specific Items

- Fill in the blanks so that the program below prints

90.0.- Do you find this version easier to read than preceding ones?

- Why wouldn’t programmers always use this form of

import?____ math import ____, ____ angle = degrees(pi / 2) print(angle)Solution

from math import degrees, pi angle = degrees(pi / 2) print(angle)Most likely you find this version easier to read since it’s less dense. The main reason not to use this form of import is to avoid name clashes. For instance, you wouldn’t import

degreesthis way if you also wanted to use the namedegreesfor a variable or function of your own. Or if you were to also import a function nameddegreesfrom another library.

Reading Error Messages

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code, and read the error message. What type of error is it?

from math import log log(0)Solution

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ValueError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-1-d72e1d780bab> in <module> 1 from math import log ----> 2 log(0) ValueError: math domain error

- The logarithm of

xis only defined forx > 0, so 0 is outside the domain of the function.- You get an error of type

ValueError, indicating that the function received an inappropriate argument value. The additional message “math domain error” makes it clearer what the problem is.

Key Points

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

A program must import a library module in order to use it.

Use

helpto learn about the contents of a library module.Import specific items from a library to shorten programs.

Create an alias for a library when importing it to shorten programs.

Analyzing Patient Data

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I process tabular data files in Python?

Objectives

Explain what a library is and what libraries are used for.

Import a Python library and use the functions it contains.

Read tabular data from a file into a program.

Select individual values and subsections from data.

Perform operations on arrays of data.

Words are useful, but what’s more useful are the sentences and stories we build with them. Similarly, while a lot of powerful, general tools are built into Python, specialized tools built up from these basic units live in libraries that can be called upon when needed.

Loading data into Python

To begin processing inflammation data, we need to load it into Python. We can do that using a library called NumPy, which stands for Numerical Python. In general, you should use this library when you want to do fancy things with lots of numbers, especially if you have matrices or arrays. To tell Python that we’d like to start using NumPy, we need to import it:

import numpy

Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to the basic Python package, much like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Just like in the lab, importing too many libraries can sometimes complicate and slow down your programs - so we only import what we need for each program.

Once we’ve imported the library, we can ask the library to read our data file for us:

numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

array([[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 3., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 2., ..., 1., 0., 1.],

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 2., 1., 1.],

...,

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 1., 1., 1.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 2., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 1., 0.]])

The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a

function call

that asks Python to run the function loadtxt which

belongs to the numpy library.

This dotted notation

is used everywhere in Python: the thing that appears before the dot contains the thing that

appears after.

As an example, John Smith is the John that belongs to the Smith family.

We could use the dot notation to write his name smith.john,

just as loadtxt is a function that belongs to the numpy library.

numpy.loadtxt has two parameters: the name of the file

we want to read and the delimiter that separates values

on a line. These both need to be character strings

(or strings for short), so we put them in quotes.

Since we haven’t told it to do anything else with the function’s output,

the notebook displays it.

In this case,

that output is the data we just loaded.

By default,

only a few rows and columns are shown

(with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays).

Note that, to save space when displaying NumPy arrays, Python does not show us trailing zeros,

so 1.0 becomes 1..

Our call to numpy.loadtxt read our file

but didn’t save the data in memory.

To do that,

we need to assign the array to a variable. In a similar manner to how we assign a single

value to a variable, we can also assign an array of values to a variable using the same syntax.

Let’s re-run numpy.loadtxt and save the returned data:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

This statement doesn’t produce any output because we’ve assigned the output to the variable data.

If we want to check that the data have been loaded,

we can print the variable’s value:

print(data)

[[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 3. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. 2. ..., 1. 0. 1.]

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 2. 1. 1.]

...,

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 1. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0. ..., 0. 2. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 1. 1. 0.]]

Now that the data are in memory,

we can manipulate them.

First,

let’s ask what type of thing data refers to:

print(type(data))

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

The output tells us that data currently refers to

an N-dimensional array, the functionality for which is provided by the NumPy library.

These data correspond to arthritis patients’ inflammation.

The rows are the individual patients, and the columns

are their daily inflammation measurements.

Data Type

A Numpy array contains one or more elements of the same type. The

typefunction will only tell you that a variable is a NumPy array but won’t tell you the type of thing inside the array. We can find out the type of the data contained in the NumPy array.print(data.dtype)float64This tells us that the NumPy array’s elements are floating-point numbers.

With the following command, we can see the array’s shape:

print(data.shape)

(60, 40)

The output tells us that the data array variable contains 60 rows and 40 columns. When we

created the variable data to store our arthritis data, we did not only create the array; we also

created information about the array, called members or

attributes. This extra information describes data in the same way an adjective describes a noun.

data.shape is an attribute of data which describes the dimensions of data. We use the same

dotted notation for the attributes of variables that we use for the functions in libraries because

they have the same part-and-whole relationship.

If we want to get a single number from the array, we must provide an index in square brackets after the variable name, just as we do in math when referring to an element of a matrix. Our inflammation data has two dimensions, so we will need to use two indices to refer to one specific value:

print('first value in data:', data[0, 0])

first value in data: 0.0

print('middle value in data:', data[30, 20])

middle value in data: 13.0

The expression data[30, 20] accesses the element at row 30, column 20. While this expression may

not surprise you,

data[0, 0] might.

Programming languages like Fortran, MATLAB and R start counting at 1

because that’s what human beings have done for thousands of years.

Languages in the C family (including C++, Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0

because it represents an offset from the first value in the array (the second

value is offset by one index from the first value). This is closer to the way

that computers represent arrays (if you are interested in the historical

reasons behind counting indices from zero, you can read

Mike Hoye’s blog post).

As a result,

if we have an M×N array in Python,

its indices go from 0 to M-1 on the first axis

and 0 to N-1 on the second.

It takes a bit of getting used to,

but one way to remember the rule is that

the index is how many steps we have to take from the start to get the item we want.

In the Corner

What may also surprise you is that when Python displays an array, it shows the element with index

[0, 0]in the upper left corner rather than the lower left. This is consistent with the way mathematicians draw matrices but different from the Cartesian coordinates. The indices are (row, column) instead of (column, row) for the same reason, which can be confusing when plotting data.

Slicing data

An index like [30, 20] selects a single element of an array,

but we can select whole sections as well.

For example,

we can select the first ten days (columns) of values

for the first four patients (rows) like this:

print(data[0:4, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 3. 1. 2. 4. 7. 8. 3.]

[ 0. 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 3. 2. 2. 6.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 3. 3. 2. 6. 2. 5. 9.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2. 1. 6. 7.]]

The slice 0:4 means, “Start at index 0 and go up to,

but not including, index 4”. Again, the up-to-but-not-including takes a bit of getting used to,

but the rule is that the difference between the upper and lower bounds is the number of values in

the slice.

We don’t have to start slices at 0:

print(data[5:10, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 2. 4. 2. 1. 6. 4.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2. 4. 2. 2. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. 5. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 5. 6. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 2. 1. 3. 5. 3. 5. 8.]]

We also don’t have to include the upper and lower bound on the slice. If we don’t include the lower bound, Python uses 0 by default; if we don’t include the upper, the slice runs to the end of the axis, and if we don’t include either (i.e., if we use ‘:’ on its own), the slice includes everything:

small = data[:3, 36:]

print('small is:')

print(small)

The above example selects rows 0 through 2 and columns 36 through to the end of the array.

small is:

[[ 2. 3. 0. 0.]

[ 1. 1. 0. 1.]

[ 2. 2. 1. 1.]]

Analyzing data

NumPy has several useful functions that take an array as input to perform operations on its values.

If we want to find the average inflammation for all patients on

all days, for example, we can ask NumPy to compute data’s mean value:

print(numpy.mean(data))

6.14875

mean is a function that takes

an array as an argument.

Not All Functions Have Input

Generally, a function uses inputs to produce outputs. However, some functions produce outputs without needing any input. For example, checking the current time doesn’t require any input.

import time print(time.ctime())Sat Mar 26 13:07:33 2016For functions that don’t take in any arguments, we still need parentheses (

()) to tell Python to go and do something for us.

Let’s use three other NumPy functions to get some descriptive values about the dataset. We’ll also use multiple assignment, a convenient Python feature that will enable us to do this all in one line.

maxval, minval, stdval = numpy.max(data), numpy.min(data), numpy.std(data)

print('maximum inflammation:', maxval)

print('minimum inflammation:', minval)

print('standard deviation:', stdval)

Here we’ve assigned the return value from numpy.max(data) to the variable maxval, the value

from numpy.min(data) to minval, and so on.

maximum inflammation: 20.0

minimum inflammation: 0.0

standard deviation: 4.61383319712

Mystery Functions in IPython

How did we know what functions NumPy has and how to use them? If you are working in IPython or in a Jupyter Notebook, there is an easy way to find out. If you type the name of something followed by a dot, then you can use tab completion (e.g. type

numpy.and then press Tab) to see a list of all functions and attributes that you can use. After selecting one, you can also add a question mark (e.g.numpy.cumprod?), and IPython will return an explanation of the method! This is the same as doinghelp(numpy.cumprod). Similarly, if you are using the “plain vanilla” Python interpreter, you can typenumpy.and press the Tab key twice for a listing of what is available. You can then use thehelp()function to see an explanation of the function you’re interested in, for example:help(numpy.cumprod).

When analyzing data, though, we often want to look at variations in statistical values, such as the maximum inflammation per patient or the average inflammation per day. One way to do this is to create a new temporary array of the data we want, then ask it to do the calculation:

patient_0 = data[0, :] # 0 on the first axis (rows), everything on the second (columns)

print('maximum inflammation for patient 0:', numpy.max(patient_0))

maximum inflammation for patient 0: 18.0

Everything in a line of code following the ‘#’ symbol is a comment that is ignored by Python. Comments allow programmers to leave explanatory notes for other programmers or their future selves.

We don’t actually need to store the row in a variable of its own. Instead, we can combine the selection and the function call:

print('maximum inflammation for patient 2:', numpy.max(data[2, :]))

maximum inflammation for patient 2: 19.0

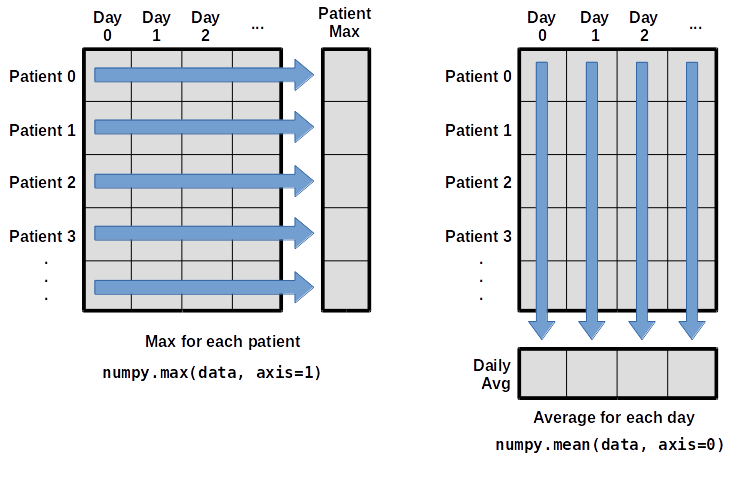

What if we need the maximum inflammation for each patient over all days (as in the next diagram on the left) or the average for each day (as in the diagram on the right)? As the diagram below shows, we want to perform the operation across an axis:

To support this functionality, most array functions allow us to specify the axis we want to work on. If we ask for the average across axis 0 (rows in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

[ 0. 0.45 1.11666667 1.75 2.43333333 3.15

3.8 3.88333333 5.23333333 5.51666667 5.95 5.9

8.35 7.73333333 8.36666667 9.5 9.58333333

10.63333333 11.56666667 12.35 13.25 11.96666667

11.03333333 10.16666667 10. 8.66666667 9.15 7.25

7.33333333 6.58333333 6.06666667 5.95 5.11666667 3.6

3.3 3.56666667 2.48333333 1.5 1.13333333

0.56666667]

As a quick check, we can ask this array what its shape is:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0).shape)

(40,)

The expression (40,) tells us we have an N×1 vector,

so this is the average inflammation per day for all patients.

If we average across axis 1 (columns in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=1))

[ 5.45 5.425 6.1 5.9 5.55 6.225 5.975 6.65 6.625 6.525

6.775 5.8 6.225 5.75 5.225 6.3 6.55 5.7 5.85 6.55

5.775 5.825 6.175 6.1 5.8 6.425 6.05 6.025 6.175 6.55

6.175 6.35 6.725 6.125 7.075 5.725 5.925 6.15 6.075 5.75

5.975 5.725 6.3 5.9 6.75 5.925 7.225 6.15 5.95 6.275 5.7

6.1 6.825 5.975 6.725 5.7 6.25 6.4 7.05 5.9 ]

which is the average inflammation per patient across all days.

Slicing Strings

A section of an array is called a slice. We can take slices of character strings as well:

element = 'oxygen' print('first three characters:', element[0:3]) print('last three characters:', element[3:6])first three characters: oxy last three characters: genWhat is the value of

element[:4]? What aboutelement[4:]? Orelement[:]?Solution

oxyg en oxygenWhat is

element[-1]? What iselement[-2]?Solution

n eGiven those answers, explain what

element[1:-1]does.Solution

Creates a substring from index 1 up to (not including) the final index, effectively removing the first and last letters from ‘oxygen’

How can we rewrite the slice for getting the last three characters of

element, so that it works even if we assign a different string toelement? Test your solution with the following strings:carpentry,clone,hi.Solution

element = 'oxygen' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'carpentry' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'clone' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'hi' print('last three characters:', element[-3:])last three characters: gen last three characters: try last three characters: one last three characters: hi

Thin Slices

The expression

element[3:3]produces an empty string, i.e., a string that contains no characters. Ifdataholds our array of patient data, what doesdata[3:3, 4:4]produce? What aboutdata[3:3, :]?Solution

array([], shape=(0, 0), dtype=float64) array([], shape=(0, 40), dtype=float64)

Stacking Arrays

Arrays can be concatenated and stacked on top of one another, using NumPy’s

vstackandhstackfunctions for vertical and horizontal stacking, respectively.import numpy A = numpy.array([[1,2,3], [4,5,6], [7, 8, 9]]) print('A = ') print(A) B = numpy.hstack([A, A]) print('B = ') print(B) C = numpy.vstack([A, A]) print('C = ') print(C)A = [[1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9]] B = [[1 2 3 1 2 3] [4 5 6 4 5 6] [7 8 9 7 8 9]] C = [[1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9] [1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9]]Write some additional code that slices the first and last columns of

A, and stacks them into a 3x2 array. Make sure toSolution

A ‘gotcha’ with array indexing is that singleton dimensions are dropped by default. That means

A[:, 0]is a one dimensional array, which won’t stack as desired. To preserve singleton dimensions, the index itself can be a slice or array. For example,A[:, :1]returns a two dimensional array with one singleton dimension (i.e. a column vector).D = numpy.hstack((A[:, :1], A[:, -1:])) print('D = ') print(D)D = [[1 3] [4 6] [7 9]]Solution

An alternative way to achieve the same result is to use Numpy’s delete function to remove the second column of A.

D = numpy.delete(A, 1, 1) print('D = ') print(D)D = [[1 3] [4 6] [7 9]]

Change In Inflammation

The patient data is longitudinal in the sense that each row represents a series of observations relating to one individual. This means that the change in inflammation over time is a meaningful concept. Let’s find out how to calculate changes in the data contained in an array with NumPy.

The

numpy.diff()function takes an array and returns the differences between two successive values. Let’s use it to examine the changes each day across the first week of patient 3 from our inflammation dataset.patient3_week1 = data[3, :7] print(patient3_week1)[0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2.]Calling

numpy.diff(patient3_week1)would do the following calculations[ 0 - 0, 2 - 0, 0 - 2, 4 - 0, 2 - 4, 2 - 2 ]and return the 6 difference values in a new array.

numpy.diff(patient3_week1)array([ 0., 2., -2., 4., -2., 0.])Note that the array of differences is shorter by one element (length 6).

When calling

numpy.diffwith a multi-dimensional array, anaxisargument may be passed to the function to specify which axis to process. When applyingnumpy.diffto our 2D inflammation arraydata, which axis would we specify?Solution

Since the row axis (0) is patients, it does not make sense to get the difference between two arbitrary patients. The column axis (1) is in days, so the difference is the change in inflammation – a meaningful concept.

numpy.diff(data, axis=1)If the shape of an individual data file is

(60, 40)(60 rows and 40 columns), what would the shape of the array be after you run thediff()function and why?Solution

The shape will be

(60, 39)because there is one fewer difference between columns than there are columns in the data.How would you find the largest change in inflammation for each patient? Does it matter if the change in inflammation is an increase or a decrease?

Solution

By using the

numpy.max()function after you apply thenumpy.diff()function, you will get the largest difference between days.numpy.max(numpy.diff(data, axis=1), axis=1)array([ 7., 12., 11., 10., 11., 13., 10., 8., 10., 10., 7., 7., 13., 7., 10., 10., 8., 10., 9., 10., 13., 7., 12., 9., 12., 11., 10., 10., 7., 10., 11., 10., 8., 11., 12., 10., 9., 10., 13., 10., 7., 7., 10., 13., 12., 8., 8., 10., 10., 9., 8., 13., 10., 7., 10., 8., 12., 10., 7., 12.])If inflammation values decrease along an axis, then the difference from one element to the next will be negative. If you are interested in the magnitude of the change and not the direction, the

numpy.absolute()function will provide that.Notice the difference if you get the largest absolute difference between readings.

numpy.max(numpy.absolute(numpy.diff(data, axis=1)), axis=1)array([ 12., 14., 11., 13., 11., 13., 10., 12., 10., 10., 10., 12., 13., 10., 11., 10., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13., 9., 12., 9., 12., 11., 10., 13., 9., 13., 11., 11., 8., 11., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13., 11., 11., 13., 11., 13., 13., 10., 9., 10., 10., 9., 9., 13., 10., 9., 10., 11., 13., 10., 10., 12.])

Key Points

Import a library into a program using

import libraryname.Use the

numpylibrary to work with arrays in Python.The expression

array.shapegives the shape of an array.Use

array[x, y]to select a single element from a 2D array.Array indices start at 0, not 1.

Use

low:highto specify aslicethat includes the indices fromlowtohigh-1.Use

# some kind of explanationto add comments to programs.Use

numpy.mean(array),numpy.max(array), andnumpy.min(array)to calculate simple statistics.Use

numpy.mean(array, axis=0)ornumpy.mean(array, axis=1)to calculate statistics across the specified axis.

Visualizing Tabular Data

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I visualize tabular data in Python?

How can I group several plots together?

Objectives

Plot simple graphs from data.

Group several graphs in a single figure.

Visualizing data

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and

the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire

lecture of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While

there is no official plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto standard. First, we will

import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a

heat map of our data:

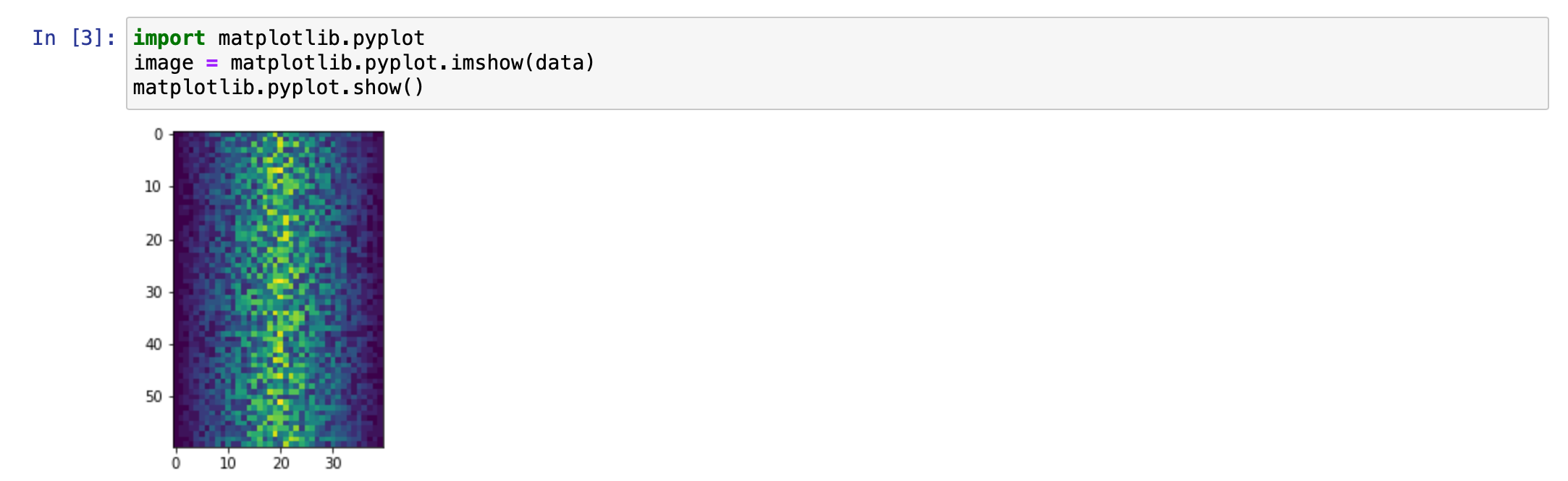

import matplotlib.pyplot

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Blue pixels in this heat map represent low values, while yellow pixels represent high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period. Let’s take a look at the average inflammation over time:

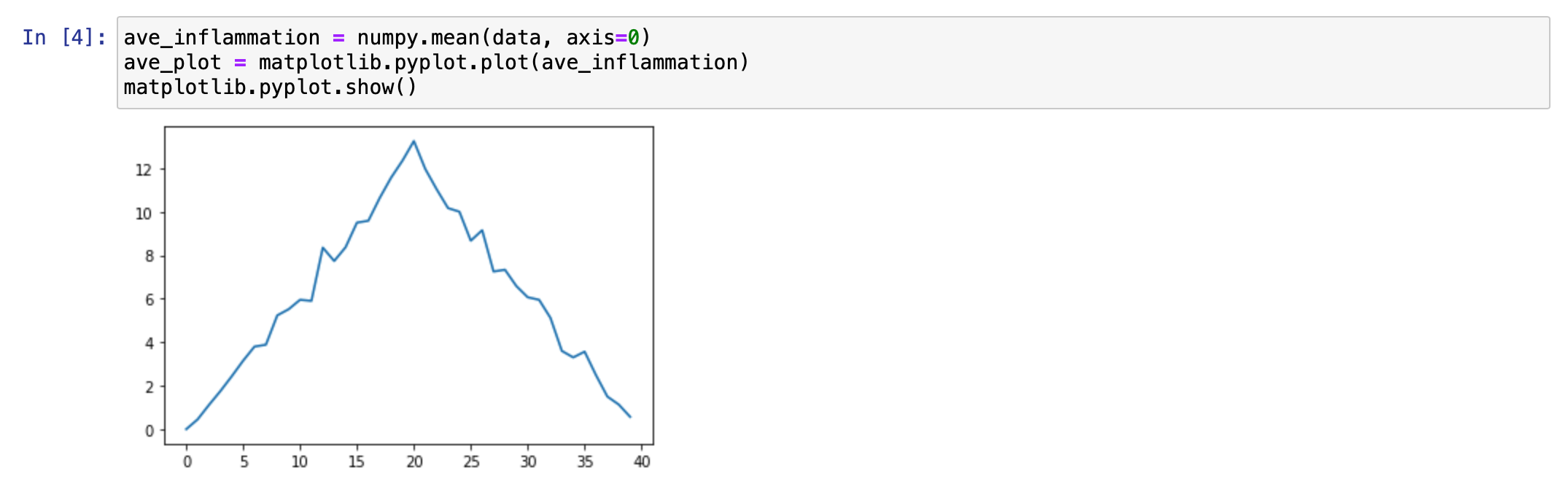

ave_inflammation = numpy.mean(data, axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Here, we have put the average inflammation per day across all patients in the variable

ave_inflammation, then asked matplotlib.pyplot to create and display a line graph of those

values. The result is a roughly linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: we might instead expect

a sharper rise and slower fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

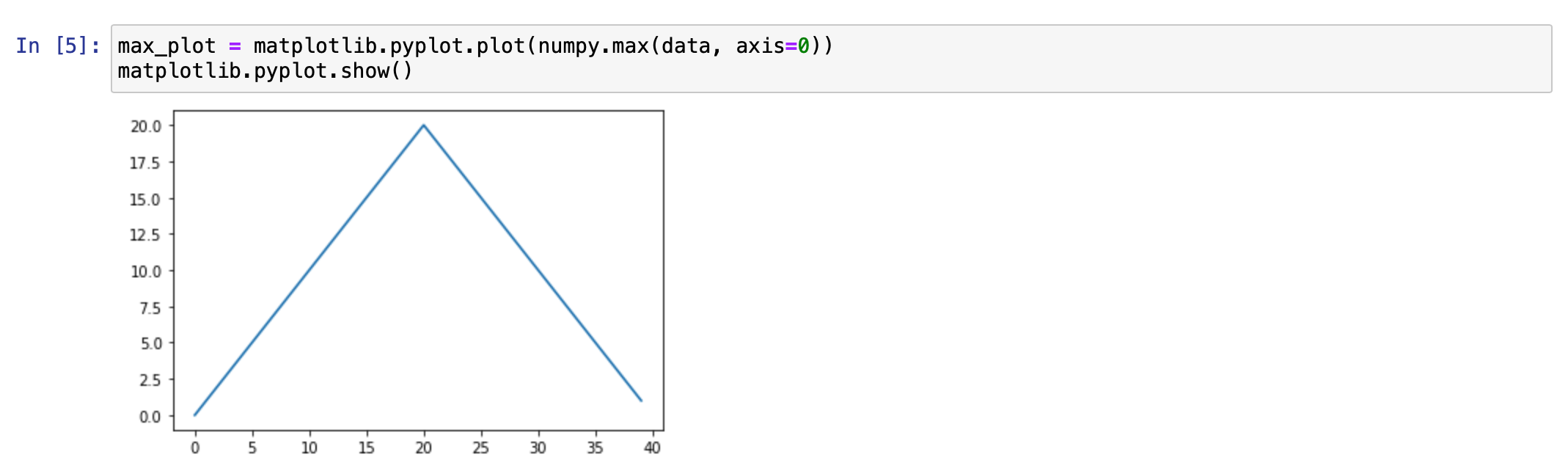

max_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

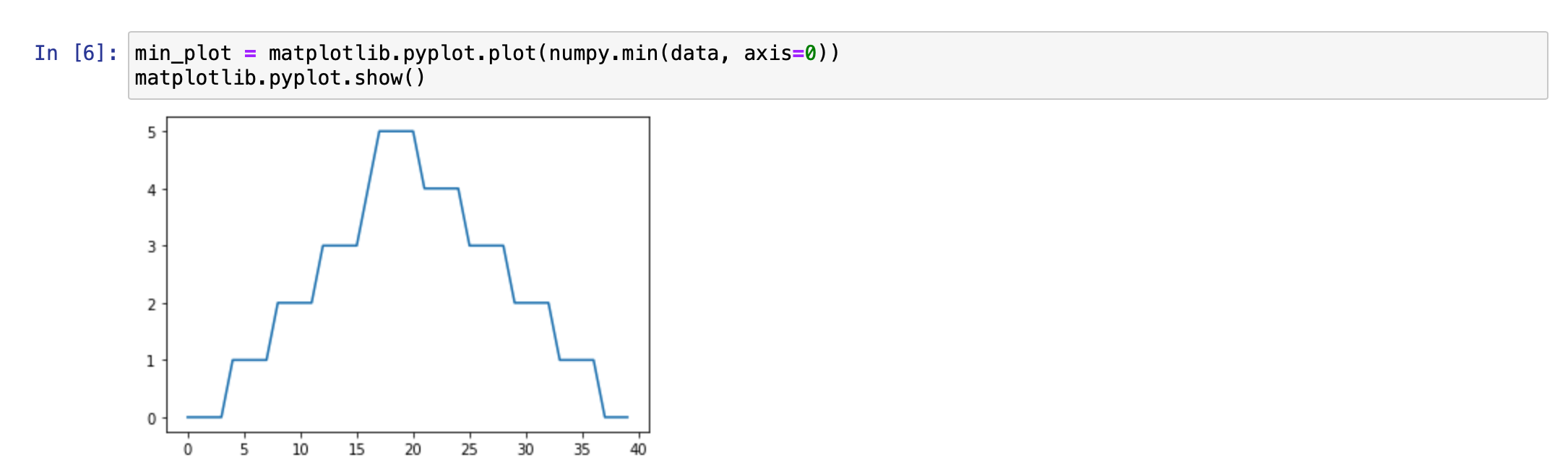

min_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The maximum value rises and falls smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither trend seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data. This insight would have been difficult to reach by examining the numbers themselves without visualization tools.

Grouping plots

You can group similar plots in a single figure using subplots.

This script below uses a number of new commands. The function matplotlib.pyplot.figure()

creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize

tells Python how big to make this space. Each subplot is placed into the figure using

its add_subplot method. The add_subplot method takes 3

parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter

refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameter denotes which subplot

your variable is referencing (left-to-right, top-to-bottom). Each subplot is stored in a

different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3). Once a subplot is created, the axes can

be titled using the set_xlabel() command (or set_ylabel()).

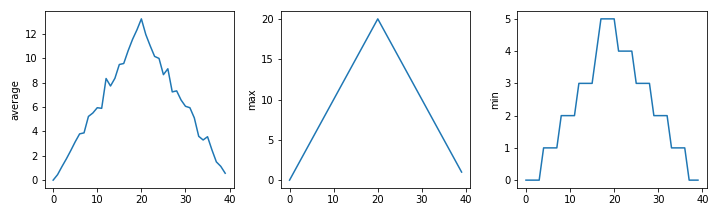

Here are our three plots side by side:

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.savefig('inflammation.png')

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The call to loadtxt reads our data,

and the rest of the program tells the plotting library

how large we want the figure to be,

that we’re creating three subplots,

what to draw for each one,

and that we want a tight layout.

(If we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(),

the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

The call to savefig stores the plot as a graphics file. This can be

a convenient way to store your plots for use in other documents, web

pages etc. The graphics format is automatically determined by

Matplotlib from the file name ending we specify; here PNG from

‘inflammation.png’. Matplotlib supports many different graphics

formats, including SVG, PDF, and JPEG.

Importing libraries with shortcuts

In this lesson we use the

import matplotlib.pyplotsyntax to import thepyplotmodule ofmatplotlib. However, shortcuts such asimport matplotlib.pyplot as pltare frequently used. Importingpyplotthis way means that after the initial import, rather than writingmatplotlib.pyplot.plot(...), you can now writeplt.plot(...). Another common convention is to use the shortcutimport numpy as npwhen importing the NumPy library. We then can writenp.loadtxt(...)instead ofnumpy.loadtxt(...), for example.Some people prefer these shortcuts as it is quicker to type and results in shorter lines of code - especially for libraries with long names! You will frequently see Python code online using a

pyplotfunction withplt, or a NumPy function withnp, and it’s because they’ve used this shortcut. It makes no difference which approach you choose to take, but you must be consistent as if you useimport matplotlib.pyplot as pltthenmatplotlib.pyplot.plot(...)will not work, and you must useplt.plot(...)instead. Because of this, when working with other people it is important you agree on how libraries are imported.

Plot Scaling

Why do all of our plots stop just short of the upper end of our graph?

Solution

Because matplotlib normally sets x and y axes limits to the min and max of our data (depending on data range)

If we want to change this, we can use the

set_ylim(min, max)method of each ‘axes’, for example:axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Update your plotting code to automatically set a more appropriate scale. (Hint: you can make use of the

maxandminmethods to help.)Solution

# One method axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Solution

# A more automated approach min_data = numpy.min(data, axis=0) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(min_data) axes3.set_ylim(numpy.min(min_data), numpy.max(min_data) * 1.1)

Drawing Straight Lines

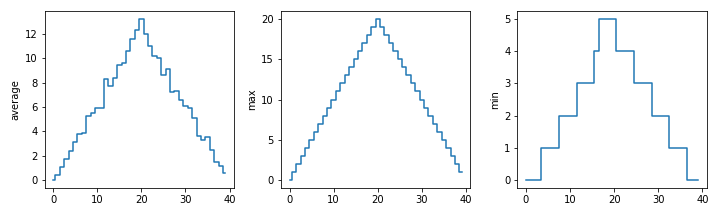

In the center and right subplots above, we expect all lines to look like step functions because non-integer value are not realistic for the minimum and maximum values. However, you can see that the lines are not always vertical or horizontal, and in particular the step function in the subplot on the right looks slanted. Why is this?

Solution

Because matplotlib interpolates (draws a straight line) between the points. One way to do avoid this is to use the Matplotlib

drawstyleoption:import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0)) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Make Your Own Plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation (

numpy.std) of the inflammation data for each day across all patients.Solution

std_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.std(data, axis=0)) matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Moving Plots Around

Modify the program to display the three plots on top of one another instead of side by side.

Solution

import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') # change figsize (swap width and height) fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(3.0, 10.0)) # change add_subplot (swap first two parameters) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Key Points

Use the

pyplotmodule from thematplotliblibrary for creating simple visualizations.

Reading Tabular Data into DataFrames

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I read tabular data?

Objectives

Import the Pandas library.

Use Pandas to load a simple CSV data set.

Get some basic information about a Pandas DataFrame.

Use the Pandas library to do statistics on tabular data.

- Pandas is a widely-used Python library for statistics, particularly on tabular data.

- Borrows many features from R’s dataframes.

- A 2-dimensional table whose columns have names and potentially have different data types.

- Load it with

import pandas as pd. The alias pd is commonly used for Pandas. - Read a Comma Separated Values (CSV) data file with

pd.read_csv.- Argument is the name of the file to be read.

- Assign result to a variable to store the data that was read.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv')

print(data)

country gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 \

0 Australia 10039.59564 10949.64959 12217.22686

1 New Zealand 10556.57566 12247.39532 13175.67800

gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972 gdpPercap_1977 gdpPercap_1982 \

0 14526.12465 16788.62948 18334.19751 19477.00928

1 14463.91893 16046.03728 16233.71770 17632.41040

gdpPercap_1987 gdpPercap_1992 gdpPercap_1997 gdpPercap_2002 \

0 21888.88903 23424.76683 26997.93657 30687.75473

1 19007.19129 18363.32494 21050.41377 23189.80135

gdpPercap_2007

0 34435.36744

1 25185.00911

- The columns in a dataframe are the observed variables, and the rows are the observations.

- Pandas uses backslash

\to show wrapped lines when output is too wide to fit the screen.

File Not Found

Our lessons store their data files in a

datasub-directory, which is why the path to the file isdata/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv. If you forget to includedata/, or if you include it but your copy of the file is somewhere else, you will get a runtime error that ends with a line like this:FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv'

Use index_col to specify that a column’s values should be used as row headings.

- Row headings are numbers (0 and 1 in this case).

- Really want to index by country.

- Pass the name of the column to

read_csvas itsindex_colparameter to do this.

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv', index_col='country')

print(data)

gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 \

country

Australia 10039.59564 10949.64959 12217.22686 14526.12465

New Zealand 10556.57566 12247.39532 13175.67800 14463.91893

gdpPercap_1972 gdpPercap_1977 gdpPercap_1982 gdpPercap_1987 \

country

Australia 16788.62948 18334.19751 19477.00928 21888.88903

New Zealand 16046.03728 16233.71770 17632.41040 19007.19129

gdpPercap_1992 gdpPercap_1997 gdpPercap_2002 gdpPercap_2007

country

Australia 23424.76683 26997.93657 30687.75473 34435.36744

New Zealand 18363.32494 21050.41377 23189.80135 25185.00911

Use the DataFrame.info() method to find out more about a dataframe.

data.info()